This will be my last post in the “JavaScript for (C/)AL Developers” series today. If I continued blogging about nearly pure JavaScript stuff, you could reasonably ask if this is in fact an NAV blog or a JavaScript one. It’s still NAV, and while the stuff I am about to write about is purely a JavaScript concept, I find it highly relevant for any control add-in developer. So, hold my beer, and bear with me for another one.

One of the complaints I often hear about JavaScript is that in JavaScript there is no encapsulation. This is almost completely true, except for the fact that it’s entirely false.

Where is the problem in the first place, and then what is the solution? Let’s dive in.

The problem

Imagine you are declaring a constructor. Imagine for a second that we are in ES5 world (that we, unfortunately, have to use if we want our control add-ins to be fully compatible with all platforms on which both NAV and Business Central are supported).

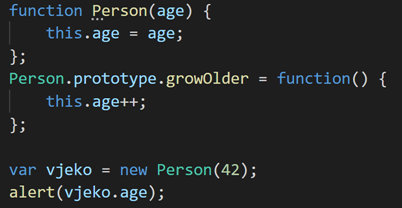

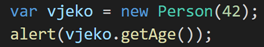

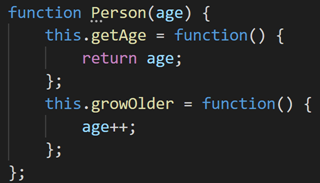

This is my code:

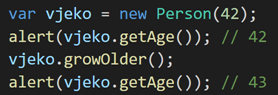

Obviously, this shows 42, which is my current age.

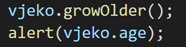

Soon, it will be my birthday, so this would show 43:

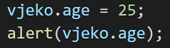

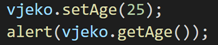

Now, while I would absolutely love to be able to do something like this in real life:

… that’s not going to happen. In a decent object-oriented world, “age” should be an encapsulated property, and you shouldn’t be able to call vjeko.age = 25 at all. C# and “normal” object-oriented languages have a concept of encapsulation, they can handle this using private fields, but JavaScript has no concept of private. Anything defined on this inside the object constructor (or later on an instance of a constructed object) is fully accessible to all code that has access to that instance. In my example above, anyone can set age and get away with it.

You could say that JavaScript has no encapsulation. And as I said above, you’d be entirely wrong.

The solution

As obvious as it is that we can’t declare anything as private directly, there are still things we can use. One beautiful concept that comes in handy is called closures. Closures are explained at length on a million of blogs, documentation sites, and code examples all over the internet, and you can google the bejesus out of them at your own pace, so I won’t delve into explaining closures here. I’ll simply jump right into applying them to solving the encapsulation problem.

There are at least two ways how you could handle this. Let’s first do the more obvious one: an access function.

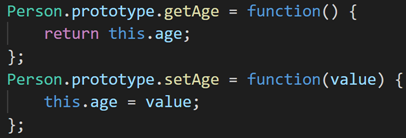

Imagine the world without properties where you cannot do object.property = value (like vjeko.age = 25 in our case, as much as I’d totally love it!). In that world, you’d have getter and setter functions:

(ignore for a moment the fact that I am still using this.age to “encapsulate” the “property”)

Obviously, you’d be able to call these like this:

Then, if you wanted to have age as read-only, you’d simply drop the setAge setter function. If this.age was really private (which it isn’t), this would do the trick for you. The problem is, nothing defined on this is private, it’s accessible to anybody having access to any instance of the object. It’s as public as it gets.

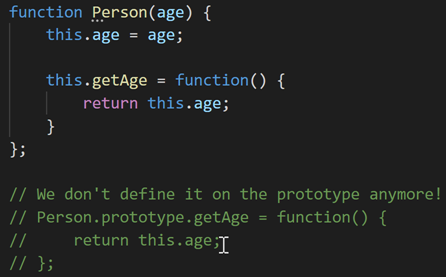

To fix this problem, the first thing we need to do is move the getter function declaration from the prototype to the instance. Prototype members are closest to what we would call static in C#, even though in runtime they have certain behavioral traits of both static and instance members. However, let’s first move the member away from the prototype, and onto instance:

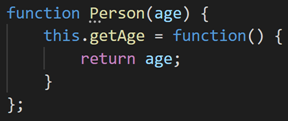

This solves only the first part of the problem, the fact that getAge was defined on the prototype rather than on the instance. However, with a simple change like this:

… we solve the problem entirely:

Age is now fully encapsulated. You can access it through the getter function, but you cannot set it directly because it’s only accessible in the closure scope of the this.getAge instance function.

To fully implement the Person class, you need to move the growOlder function from the prototype into the instance:

And this works exactly as you want it to work:

But why does it work? It works because of closures. The age parameter from the constructor was captured in the closure scope of both getAge and growOlder functions, allowing you to access its value from both of these functions, but making it completely inaccessible to anybody else, anywhere else.

Even better solution

You could say that you don’t want to access it through a getter function, and that you require full-blown read-only property syntax. You want your age read-only and encapsulated at the same time. Gotcha! JavaScript can’t encapsulate that! Except that it absolutely can.

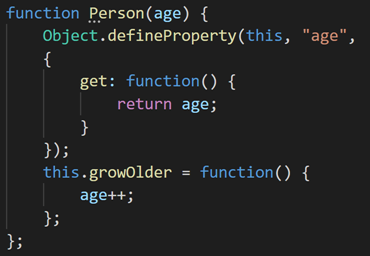

I addressed the Object.defineProperty method in my previous post, and if you read that one, you can immediately see how it can be applied here.

So, let’s define a read-only instance property of Person class:

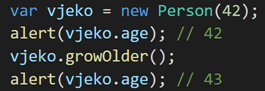

There. It didn’t hurt. And it works:

So there you have it. Full-blown encapsulation in JavaScript to help you write good, isolated code, and take your control add-ins to real kick-a$$ level.

Happy JavaScripting, and I hope to get more time to blog about other cool and useful JavaScript tips and tricks for (C/)AL developers.

Hi great blog , thank

I would like to encourage everyone who wants to build NAV-oriented solutions to look at modern front-end ecosystem where problems like compatibility with ES5 have already been solved by tools like babel. You don’t need to write ES5 code any more to be able to ship it to ES5 environment (what we, front-end devs, still need to do). You could introduce a build process where your codebase based on modules and classes could be compiled/transpiled/translated by tools which are able to convert modern language constructs to older patterns. Modern JavaScript feels no longer that odd when comparing to other languages.

See more details here: https://babeljs.io/docs/en/usage

Good point, Przemek. And actually some of this aspects I actually have in my to-do list for today 😉

Pingback: Encapsulation in JavaScript - Microsoft Dynamics NAV Community