In my

previous post, I’ve written about the situation when you (or somebody you trust) redeclares the

$ variable, thus inadvertently breaking all your jQuery code. I’ve also explained how to remedy for it inside the code you write by applying the

Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE) or

Self-Executing Anonymous Function pattern.

However, is there anything you can do to prevent anyone from trampling over

$ or

jQuery variables in the first place?

As I said in my last post, yes, and no.

Let’s take a closer look at it.

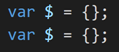

Redeclaration

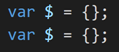

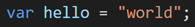

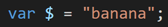

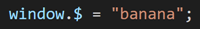

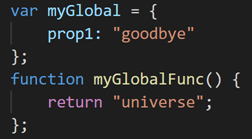

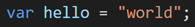

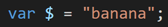

As you know by now, any variable in JavaScript can be happily redeclared. You can do this as often and as much as you want:

As much as you can do it, anyone else can do it, too. If you don’t control all of the scripts you load in your control add-in (or web page for that matter) there is no way you can prevent anyone from redeclaring any variable they want. That’s just how JavaScript works. Sorry, it’s not

just how JavaScript works, it’s also a very useful feature, which allows you to write safe code, fallback code, mock code, and there are probably a million other use cases where redeclaration is a useful feature.

But obviously, redeclaration can be a cause of bugs. You can cause a bug in somebody else’s script if you redeclare their global variables, others can cause bugs in your script by redeclaring your variables, anyone can cause problems in all other scripts by redeclaring common library variables such as

jQuery or

$.

Global scope in browser?

You might have a notion of what global scope is. Simply put, it’s variables (and functions) that are available to all of script code anywhere in a browser window. If you are not within a function scope, what you declare is declared in global scope. Unless you do anything, all of your code loaded with <script> tags, if not made a part of a function, is declared in the global scope, and all of the functions and variables are accessible to all other scripts.

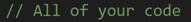

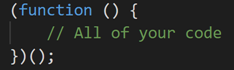

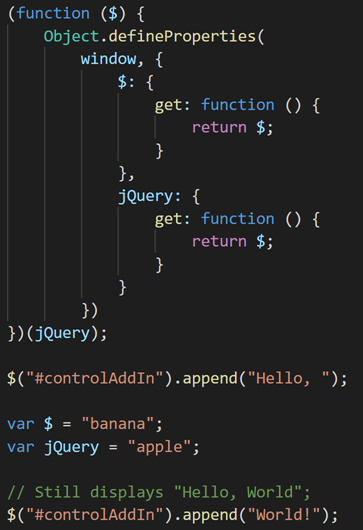

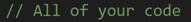

If you are not writing your own libraries (that is: code that you want to be invoked from other scripts), then it’s a very good idea to embed all of your code in an IIFE, like this. Simply put, instead of doing this:

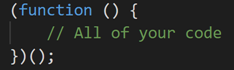

… you should do this:

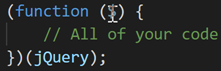

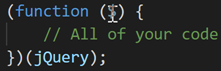

If it uses jQuery, obviously, you should do this:

When you do this, you don’t change the behavior of your own code, but you isolate it from other scripts so that no other script can trample over anything inside your script, and your variable and functions inside your script are safe from redeclaration in other scripts.

However, this may not be good enough. You may be required to put stuff into global scope. For example, you are writing your own library, or you are writing a control add-in where interface functions must be available in the global scope. Also, you may be using third-party libraries (such as jQuery) and anyone else can inadvertently trample over your (or library) globals.

What then?

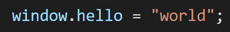

Well, let’s take a look at something else about the global scope in browser: all identifiers in the global scope are properties of the

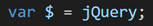

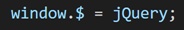

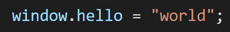

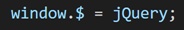

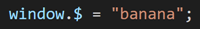

window object. This means that when you do this:

… you are, in fact, doing this:

(truthfully speaking, it’s a tiny little bit more complicated than this, but the overall effect is that)

This is true of browser, but it’s not true of all JavaScript runtimes (it’s certainly not true about

Node.js, and may be true or false about any other JavaScript runtimes out there).

In essence, any global variable or function is a

property of the

window object.

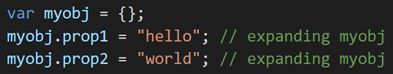

Properties in JavaScript

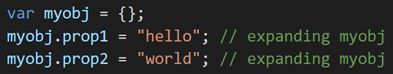

In JavaScript, you can define object properties directly by expanding the object’s definition:

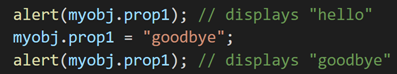

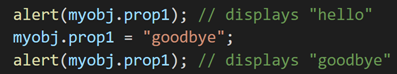

However, properties defined this way are weak, and anyone can change them:

This is, in a way, what you expect. You assign one value, then assign another value, and of course the second assignment successfully assigns the new value. The same happens with variable declarations. Since this:

… equals this:

… then redeclaring it like this:

… simply assigns a new value to the

window object property:

You can’t really prevent anyone from assigning any value they want to a property that was

expanded on an object using the

.property = value syntax.

However, since the

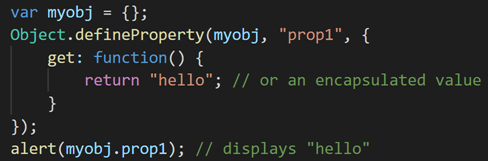

ES5 version, you can define object properties using a more robust feature:

Object.defineProperty method. This method allows you far more control about property functionality, such as whether you can change a value, if the property is read/write or read-only or write-only, and more.

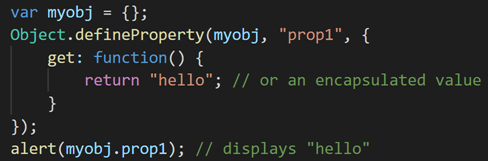

For example, to define a read-only property, you could do this:

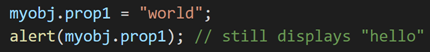

Then, reassigning

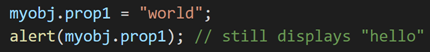

myobj.prop1 to some other value won’t have any effect:

Protecting your variables (or jQuery)

Obviously, you can use this ES5

Object prototype feature to protect your own variable declarations. If you are creating a library that you don’t want anyone to trample over, instead of simply declaring them in the global scope, you could define them as read-only

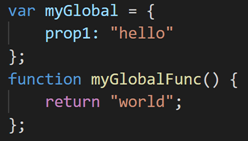

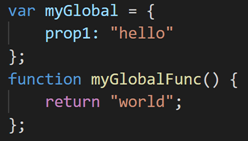

window object properties. This means, instead of this:

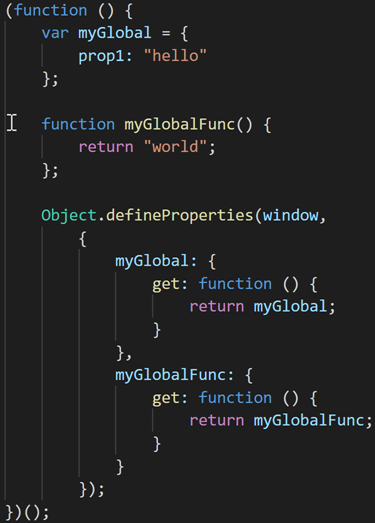

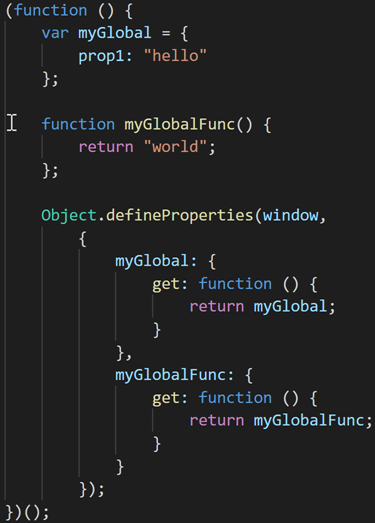

… do this:

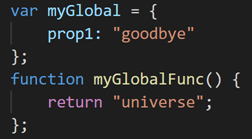

This will prevent anybody from (successfully) doing this in their script:

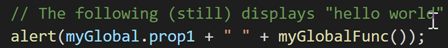

… while still allowing you to do this, with expected results:

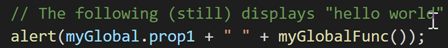

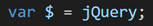

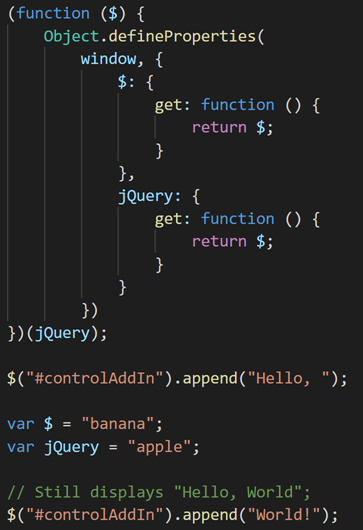

Obviously, you can apply the same principle with

jQuery and

$ variables. You could simply write this, and nobody can trample over your

$ or

jQuery identifiers:

Now that you know how to prevent anyone trampling over

$ or

jQuery identifiers, you could do it in a more generic way: create a script that does nothing but protects the

$ and

jQuery identifiers using the pattern above, and declare it in your control add-in (or your web page) immediately after declaring jQuery script, and you are safe. Your code will still run correctly without being adversely affected by anyone else’s scripts loaded after your control add-in (or page) has been loaded.

Final thoughts

This may all seem much simpler than it actually is. Depending on how you are writing your code, what’s been loaded and what hasn’t, and when, you may or may not be able to successfully do the trick explained here. For example, you can’t declare global variables and then redeclare them as explicitly declared properties on

window object using

Object.defineProperty within the same script, due to variable hoisting and the implicit behavior of the window object itself that does much more than simply expand itself on global variable or function declaration (as I stated it for simplification purposes). Another thing that can happen is that somebody else already “protects” some globals (

$ or

jQuery, for example) before you get a chance to do that, in which case your trick fails for the same reason it worked if you manage to load your script first.

Overall, the best you can do is:

- Test the third-party scripts you use

- Always encapsulate all your non-library code into IIFEs, that’s the (function() {})() pattern

- Always define your own library functionality through Object.defineProperty on window object, rather than simply declaring them in the global scope

- Never assume that $ is jQuery! Always access it from within a (function($) {})(jQuery) context (which isn’t bullet-proof, but is statistically much safer)

Good luck, and let me know if this helped (or just made it all more complicated for you).

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

As much as you can do it, anyone else can do it, too. If you don’t control all of the scripts you load in your control add-in (or web page for that matter) there is no way you can prevent anyone from redeclaring any variable they want. That’s just how JavaScript works. Sorry, it’s not just how JavaScript works, it’s also a very useful feature, which allows you to write safe code, fallback code, mock code, and there are probably a million other use cases where redeclaration is a useful feature.

But obviously, redeclaration can be a cause of bugs. You can cause a bug in somebody else’s script if you redeclare their global variables, others can cause bugs in your script by redeclaring your variables, anyone can cause problems in all other scripts by redeclaring common library variables such as jQuery or $.

As much as you can do it, anyone else can do it, too. If you don’t control all of the scripts you load in your control add-in (or web page for that matter) there is no way you can prevent anyone from redeclaring any variable they want. That’s just how JavaScript works. Sorry, it’s not just how JavaScript works, it’s also a very useful feature, which allows you to write safe code, fallback code, mock code, and there are probably a million other use cases where redeclaration is a useful feature.

But obviously, redeclaration can be a cause of bugs. You can cause a bug in somebody else’s script if you redeclare their global variables, others can cause bugs in your script by redeclaring your variables, anyone can cause problems in all other scripts by redeclaring common library variables such as jQuery or $.

… you should do this:

… you should do this:

If it uses jQuery, obviously, you should do this:

If it uses jQuery, obviously, you should do this:

When you do this, you don’t change the behavior of your own code, but you isolate it from other scripts so that no other script can trample over anything inside your script, and your variable and functions inside your script are safe from redeclaration in other scripts.

However, this may not be good enough. You may be required to put stuff into global scope. For example, you are writing your own library, or you are writing a control add-in where interface functions must be available in the global scope. Also, you may be using third-party libraries (such as jQuery) and anyone else can inadvertently trample over your (or library) globals.

What then?

Well, let’s take a look at something else about the global scope in browser: all identifiers in the global scope are properties of the window object. This means that when you do this:

When you do this, you don’t change the behavior of your own code, but you isolate it from other scripts so that no other script can trample over anything inside your script, and your variable and functions inside your script are safe from redeclaration in other scripts.

However, this may not be good enough. You may be required to put stuff into global scope. For example, you are writing your own library, or you are writing a control add-in where interface functions must be available in the global scope. Also, you may be using third-party libraries (such as jQuery) and anyone else can inadvertently trample over your (or library) globals.

What then?

Well, let’s take a look at something else about the global scope in browser: all identifiers in the global scope are properties of the window object. This means that when you do this:

… you are, in fact, doing this:

… you are, in fact, doing this:

(truthfully speaking, it’s a tiny little bit more complicated than this, but the overall effect is that)

This is true of browser, but it’s not true of all JavaScript runtimes (it’s certainly not true about Node.js, and may be true or false about any other JavaScript runtimes out there).

In essence, any global variable or function is a property of the window object.

(truthfully speaking, it’s a tiny little bit more complicated than this, but the overall effect is that)

This is true of browser, but it’s not true of all JavaScript runtimes (it’s certainly not true about Node.js, and may be true or false about any other JavaScript runtimes out there).

In essence, any global variable or function is a property of the window object.

However, properties defined this way are weak, and anyone can change them:

However, properties defined this way are weak, and anyone can change them:

This is, in a way, what you expect. You assign one value, then assign another value, and of course the second assignment successfully assigns the new value. The same happens with variable declarations. Since this:

This is, in a way, what you expect. You assign one value, then assign another value, and of course the second assignment successfully assigns the new value. The same happens with variable declarations. Since this:

… equals this:

… equals this:

… then redeclaring it like this:

… then redeclaring it like this:

… simply assigns a new value to the window object property:

… simply assigns a new value to the window object property:

You can’t really prevent anyone from assigning any value they want to a property that was expanded on an object using the .property = value syntax.

However, since the ES5 version, you can define object properties using a more robust feature: Object.defineProperty method. This method allows you far more control about property functionality, such as whether you can change a value, if the property is read/write or read-only or write-only, and more.

For example, to define a read-only property, you could do this:

You can’t really prevent anyone from assigning any value they want to a property that was expanded on an object using the .property = value syntax.

However, since the ES5 version, you can define object properties using a more robust feature: Object.defineProperty method. This method allows you far more control about property functionality, such as whether you can change a value, if the property is read/write or read-only or write-only, and more.

For example, to define a read-only property, you could do this:

Then, reassigning myobj.prop1 to some other value won’t have any effect:

Then, reassigning myobj.prop1 to some other value won’t have any effect:

… do this:

… do this:

This will prevent anybody from (successfully) doing this in their script:

This will prevent anybody from (successfully) doing this in their script:

… while still allowing you to do this, with expected results:

… while still allowing you to do this, with expected results:

Obviously, you can apply the same principle with jQuery and $ variables. You could simply write this, and nobody can trample over your $ or jQuery identifiers:

Obviously, you can apply the same principle with jQuery and $ variables. You could simply write this, and nobody can trample over your $ or jQuery identifiers:

Now that you know how to prevent anyone trampling over $ or jQuery identifiers, you could do it in a more generic way: create a script that does nothing but protects the $ and jQuery identifiers using the pattern above, and declare it in your control add-in (or your web page) immediately after declaring jQuery script, and you are safe. Your code will still run correctly without being adversely affected by anyone else’s scripts loaded after your control add-in (or page) has been loaded.

Now that you know how to prevent anyone trampling over $ or jQuery identifiers, you could do it in a more generic way: create a script that does nothing but protects the $ and jQuery identifiers using the pattern above, and declare it in your control add-in (or your web page) immediately after declaring jQuery script, and you are safe. Your code will still run correctly without being adversely affected by anyone else’s scripts loaded after your control add-in (or page) has been loaded.

Pingback: Some more thoughts about trampling over $ - Vjeko.com

Pingback: Some more thoughts about trampling over $ - Vjeko.com - Dynamics 365 Business Central/NAV User Group - Dynamics User Group

Pingback: Encapsulation in JavaScript - Vjeko.com

Pingback: Encapsulation in JavaScript - Vjeko.com - Dynamics 365 Business Central/NAV User Group - Dynamics User Group

Very good exaplanation!

How would you use a Self-Executing Anonymous Function with an anonymous function for the .ready() method?

I mean:

$(function() {

// Handler for .ready() called.

});

Which is equivalent to

$( document ).ready(function() {

// Handler for .ready() called.

});

You tell us to not assume $ is jQuery. Would that break this feature?

Like this:

(function($) {

$(document).ready(function() {

// Your document ready stuff

};

})(jQuery);

It’s all over my other posts, every single demo I posted on GitHub today and yesterday applies this.

hehe, didn’t peek into the GitHub demos yet. Just read this post once again, and then the question came up. Thanks for pointing out!

Pingback: Some more thoughts about trampling over $ - Microsoft Dynamics NAV Community